Consumer Inequality and Coffee Sovereignty in Brazil

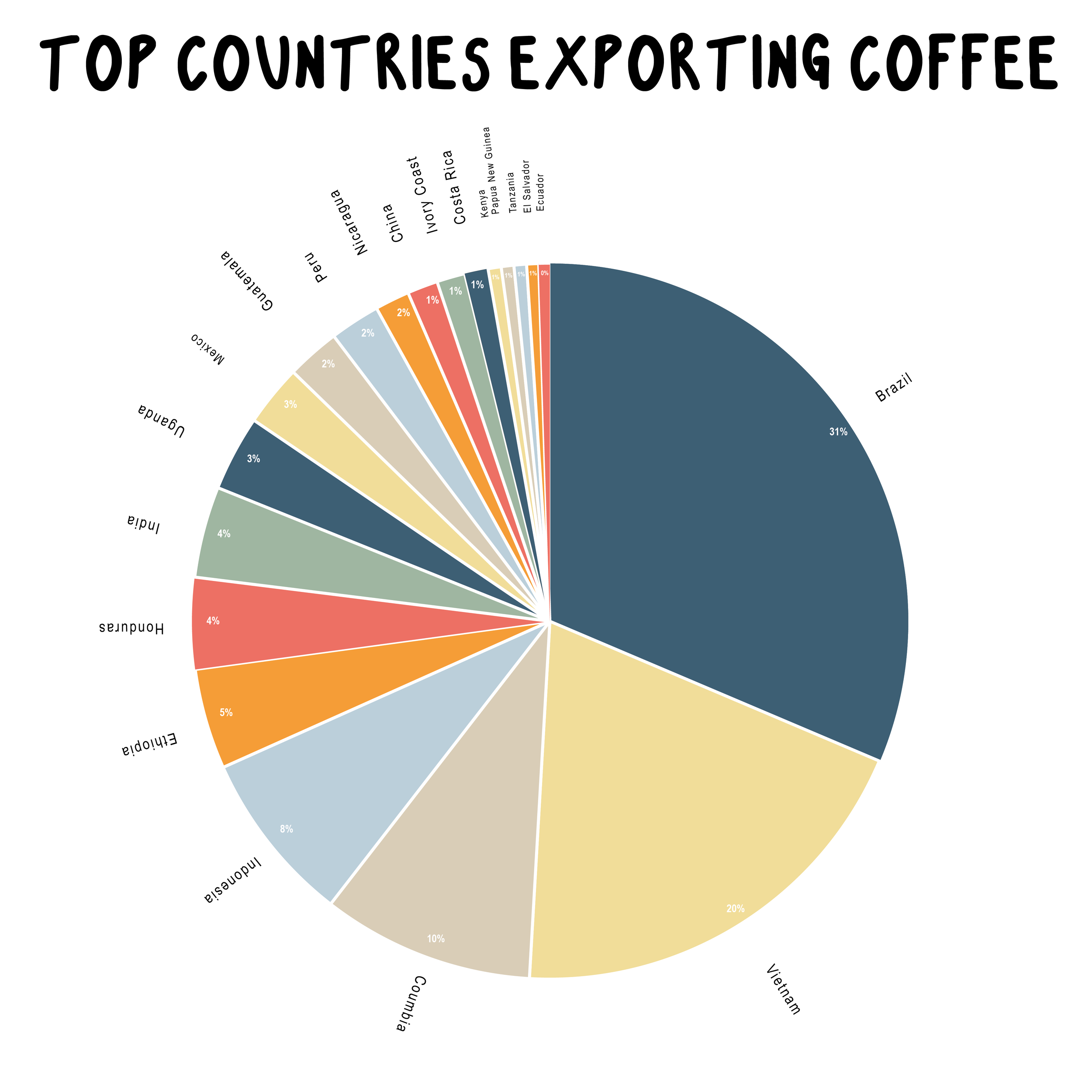

Anyone with even a passing interest in coffee knows that Brazil is the world’s largest producer of beans. Less well-known, however, is that Brazil has recently overtaken the United States as the world’s single largest consumer of coffee. This combination of high levels of production and consumption has created a hybrid coffee economy in which the demands of producers and consumers are brought closer together — and whose local shape is heavily influenced by the norms and flows of the global coffee trade where coffee moves outbound from producing countries.

In response to this changing face of global coffee consumption trends, I moved to São Paulo, Brazil, to conduct a research project which asked the question ‘How is being a specialty coffee consumer in a coffee-producing nation differ from being a consumer in a traditionally importing nation?’ While inequalities between coffee consumers and agricultural coffee producers have rightly been the focus of industry discourse around equity along the coffee supply chain, this discussion has missed the large populations who exist in these hybrid spaces like Brazil. These consumers are constrained by trade flows, laws, and economic rationales which move the very best of the coffee produced in their countries away from them and into coffee importing nations. Today, a growing movement drawing on the tenants of food sovereignty, or the right of access to culturally-appropriate and meaningful foodstuffs, is shifting the conversation around who has the right to consume a given coffee.

Proximity and Access to the Best

Living in a coffee producing country means you’re physically and socially closer to the coffee than importing nations — even if you’re surrounded by skyscrapers in the centre of São Paulo. Over half the people I worked with in my research had relatives or ancestors who currently or previously worked in coffee agriculture. Farms are only a few hours drive away — and that’s not even counting the massive urban coffee farm in Sao Paulo’s city centre! But proximity to coffee does not necessarily translate to access to coffee, especially when it comes to the choice, high-quality lots prized by the specialty industry.

As the Brazilian academic Silvia Ramos Sollai notes, ‘It is general knowledge [among Brazilians] that the best articles do not remain in Brazil; they are exported.’ This is both a general trend and something we seen borne out concretely in the case of specialty coffees: Brazilian specialty coffee enthusiasts are often painfully aware that the best coffees from their country are exported for consumption elsewhere, as foreign buyers — especially those from the United States, Europe, and East Asia — almost invariably have larger purchasing budgets than domestic specialty coffee companies. The coffees that remain in-country are the leftovers that have not been sold abroad.

To combat this pattern and compete with international buyers, Brazilian coffee roasters attempt to stay one step (and one harvest year) ahead of foreign firms: If they can get to coffees and up-and-coming farms before the international buyers can, they will at least have one season of exceptional quality coffee, before the farmers — realising the potential of their coffees, due to the interest from high-end cafés in Brazilian urban centres — begin to more actively seek higher prices abroad.

When I asked Mari, a photographer, to describe the best coffee she’d ever tasted, she replied: ‘The best coffee I’ve ever had? Well, it was last year and it was beautiful; beautiful. Of course, no one here could get it this year because the producers realised what they had and that they could sell it for more if they sold it abroad.’ Once producers realise they have in their possession a very high-quality coffee or plot, it becomes much more difficult for Brazilians to access it in future harvest years because economic rationale dictates that it will start to be channelled into international exportation and distribution networks.

As the owner of one Sao Paulo-based specialty coffee shop explained to me, this state of affairs is sustainable — but only just, and certainly not for long. ‘What can we do? [Foreigners] are always going to pay [Brazilian farmers] better than we can. We can’t change that. For now, the coffee that we can get is okay. But in the future, when our market and customer base are more developed? When our customers know that what they regularly get isn’t actually that good? What will we do then?’

Of course, Brazilian coffee farmers retain relationships with their domestic clients, and still sell them coffee — be it off-cuts of the harvest that weren’t picked up by international buyers or early experimental lots — but once foreign firms enter the purchasing picture, the reality is that less coffee from any given farm remains for domestic consumption. But, as the owner of a respected roastery told me, producers ‘will never show us the best coffees because they are holding them for international buyers, you know? If they have some coffee in abundance, they do let us taste it; but if it’s a coffee of which they only have [...] 10 bags or something, they will totally hold that for the international buyer.’

These tensions here reveal one of the ways the specialty coffee industry has often oversimplified discussions of how to engage and support producing countries: there are multiple, and sometimes conflicting, motivations and desires to consider. The seemingly predetermined outbound flow of highest-quality coffee from the nations in which it is produced does have tangible economic benefits drawn from the higher prices gained on the global market when compared to the local — but who misses out in this situation?

Coffee Sovereignty

The picture for specialty coffee consumers in Brazil is complicated, and all the more so because phytosanitary regulations in place to protect the national coffee crop from pests and disease make it nearly impossible to import green coffee into Brazil. The result is that coffees from other origins are almost never encountered in Brazil. Specialty coffee enthusiasts in Brazil drink almost exclusively Brazilian coffees, and they rarely have access to the very best quality Brazilian coffees.

‘Food sovereignty’ is the idea that groups of people (not corporations) have a right to define their own food policy, and that all communities have a right to access food that is both culturally-important and healthful. In other words, good food (produced in an ecologically and socially sustainable manner) is a right we all have.

The right to high-quality coffee from one’s own country is not, perhaps, as life-and-death as some of the questions of heritage food access or water privatisation that food sovereignty activists have approached in recent years. But it does represent what happens when an abstract global system (‘the specialty coffee market’) takes precedence over localized experience in coffee-growing nations; the fruits of regional and national agricultural heritage are not necessarily available locally, or only to a select few at great cost, and with very limited consumer control.

Brazilian consumers who both desire the best of their nation’s coffee and who believe that they have a right to consume it invoke any number of strategies to divert coffee from its outbound flow, but one of the most common ways to get high-quality Brazilian coffee is to buy it from foreign roasters after it has been exported and roasted, and then re-import it — hardly a sustainable solution. When I asked one barista why she spent such a considerable portion of her wages importing Brazilian coffee from European and American roasters, she replied simply: ‘I deserve this coffee as much as you do.’

A cohesive ‘coffee sovereignty’ solution will not arise from all consumers in importing nations suddenly ceasing to drink coffee in order to divert its trajectories domestically (this would, after all, destroy the livelihoods of farmers globally). Rather, we are at an earlier stage of development, one which calls for reflection, discussion, and contemplation as to how we shape a coffee future which is equitable for the many types of producers and the many types of consumers who exist in relation to specialty coffee. And so, I suggest simply that you consider with your next cup of coffee the questions: Who is not drinking this coffee? Who could be drinking this coffee? Am I more deserving of this coffee than anyone else?