How To Make Cider

When Burum Met Pomona – A Case Study

How is cider made?

A question that will give even the most versed cider enthusiast pause before answering.

Simply the fruit is broken down, squeezed until the juice runs out, and then, if left long enough, the natural yeast will start to ferment the sugars within the juice, turning them into alcohol and C02, with the end product becoming cider.

For most makers in the UK, cider production can only be done once a year, when the apples are ripe and ready. Harvest can start as early as August, or as late as October. This range of start date depends on most importantly the apple variety, but also the orchard's location, its altitude and microclimate, and also the weather that particular year. In general however, apples tend to fall from August to November in the Northern Hemisphere, starting with dessert or more acid-led fruit, and ending with the more bitter and tannic varieties.

To help us write this piece, we decided that the best way to explain how cider is made would be to make a cider ourselves, and document that process as a case study. In this piece we’re going to be looking at the lifespan of a bottle of cider, with a look at our collaboration with Little Pomona, Herefordshire. Little Pomona was set up in 2015 by James and Susanna Forbes, moving to its current location on Brook House Farm in 2019.

I was lucky enough to join Little Pomona for the whole of the Harvest 2021, to experience every step, and to explore what choices had to be made along the way.

From the beginning it was important to all of us that we made decisions according to the fruit. We didn’t start the project with an idea of a final product, other than the fact that we wanted to keep things simple, picking a single variety, from one orchard. We wanted to let the fruit lead us in our choices, to take the project in stages, and to taste every step of the way.

Picking (and shaking)

Picking the fruit is the first step to making cider. Some makers use machinery to help them shake the trees and gather the fruit, but smaller makers will handpick their fruit - with the help of a panking pole of course.

What's a panking pole?

Well, a panking pole is a pole with a hook on the end, the hook is used on a branch to (gently) shake the apple tree. This action works to loosen fruit from the trees. Commercial orchards are grown more densely, with less space between the trees and between the rows than in traditional orchards, and often on so-called dwarf rootstock, which means that the trees are not so tall, and the fruit picker is able to shake the trees by hand.

There are benefits to both machine harvesting and hand harvesting, but a big positive to hand harvesting is quality control in the orchard. The picker is able to select which apples will be allowed onto the sorting table.

In the July before harvest of 2021, we agreed as a team that we would pick from the orchard behind the cidery on Brook House Farm, where there are rows and rows of Dabinett apples which that year had been left unsprayed - one of the many decisions a commercial grower much make. These bittersweet apples have a reputation of harvesting well, and we wanted to have enough juice from one apple variety from one orchard to be able to focus on a single variety.

We spent a few days panking the trees, and handpicking all of the apples as they fell to the ground. Carefully sorting through them to avoid any rotten, over-bruised or wasp-stung apples.

Washing (and sorting)

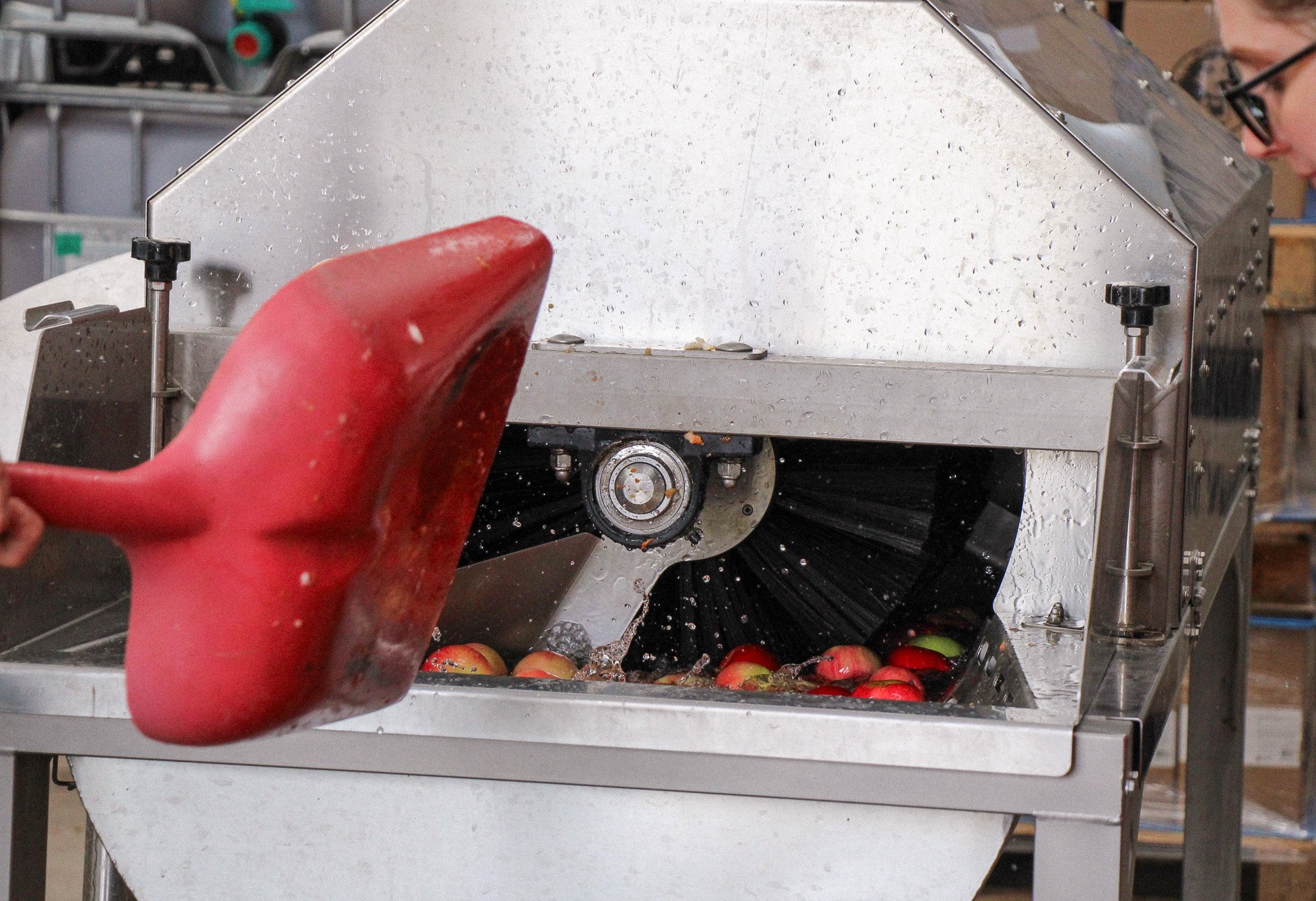

The next stage of cider making is washing the fruit. This is to ensure that the fruit is free of dirt, wildlife, and shrubbery. Some makers wash their fruit in large baths of water, sorting and separating into fruit crates. Little Pomona however have their own washer machine.

With a constant flow of ever-changing water, the benefit to the washer is that it contains a large rotating brush that works to help shift any dirt or debris from the fruit. Going the extra mile, Little Pomona have a sorting table to do a secondary check of the fruit going into the washer, and another sorting table between the washer and the scratter. This is the last time the fruit can be checked before it makes its way into the scratter.

This could, to some, be viewed as overkill. But for James and Susanna, it is vital to do all that can be done to preserve the delicate aromatics of the fruit, as well as to minimise the risk from bacterial spoilage and other unwanted microbial activity. This holds true to their zero sulphite regime if at all possible, sulphites being the normal solution due to their anti-microbial and anti-oxidative properties.

This means they need to put in as much work as possible in the run up to pressing to ensure that the cider won’t be spoiled in any way. The cleaner the fruit, the less chemical assistance the cider needs to remain stable once bottled.

Pressing (and scratting)

The milling of the fruit then happens in what is known as a scratter. A scratter chops up the apples, turning them into pulp, and it is this that gets pressed.

The pulp then chugs through a big tube – very reminiscent of Charlie and the Chocolate factory - to be carried into the press.

All makers have different ways of pressing apples for cider, but the end result is always juice.

At Little Pomona they have invested in a pneumatic press, a lightly modified version of the sort of press that is used to press grapes for wine. This works by funnelling the pulp into a strong, cylindrical membrane, to which pressure is applied, and the membrane then intermittently contracts, expands and rotates. This extracts juice from the pulp, which is channelled from the membrane, running off into a stainless steel "bath" before being pumped through a pipe connected to a fermentation vessel.

James and the cidermaking team will decide which sort of fermentation vessel to choose, depending on the apple - or pear - varieties and their characteristics, the volume of juice available, and the plan at this stage. It could be either a stainless steel tank, or an IBC, a large, inert plastic cube which holds either 640 or 1000 litres. Or, rarely, juice might go into an oak barrel.

Fermentation (and beyond)

Fermentation is the process of sugar turning into alcohol and C02, which happens very easily with fresh apple juice due to its high sugar content and the ever present supply of yeast. As well as yeasts in the cidery atmosphere, apples also have their own yeasts growing on the skins and in the pulp, so when they are pressed, those yeasts are poised to consume the sugar and kick off fermentation.

(A yeasty aside: this process is called primary fermentation, and most makers will allow this process to be completed in a fermentation tank before deciding on the next step and eventually bottling. However some makers decide that they'd like to capture a little bit of natural fizz in the bottle, and so will follow fermentation very carefully, and bottle before all the sugar has fermented. Thus the cider will finish fermenting in the bottle, capturing the fizz within the bottle. In wine making, this is called pétillant naturel, resulting in what we know as Pét Nat.)

All the sugars in apples are fermentable, so once fermentation is over, the cider will be naturally dry, and it's time for the next decision. Will the new cider be bottled or packaged straight away, or will it be conditioned. If the latter, the cider will be transferred into a separate vessel for conditioning. All cider makers choose to condition in different ways, and for Little Pomona they have the option of conditioning in stainless steel, or wooden barrels that have been previously used for wine, sherry, bourbon or cognac. Each of these vessels will have different effects on the end flavour and mouthfeel of the cider. Barrels, for example, allow the cider to "breathe", giving a chance for tannins to soften over time.

Conditioning can take many months, but the best way for a cider maker to know if their cider is ready to package is to taste it! Cider makers then need to decide how they would like to package their product, either in cans, bottles, bag in boxes, kegs, or a mixture of all of these.

The Burum Pair Of Ciders

For the ciders that we made with Little Pomona, we knew that we had enough juice to potentially do two different ciders, which we saw as an opportunity to present Dabinett from the same orchard, in the same year, in two different ways.

Once the juice was pressed and fermented, we decided to condition half of the juice in a steel fermentation vessel, with two-thirds of the other half going into two ex-Chardonnay barrels, and the final third going into an ex-Cognac barrel. Steel tends not to add flavours, whereas the different oaks have an effect on developing flavour as well as letting the tannins soften.

From there we tasted the Chardonnay barrels and were thrilled with the results. This needed no further adjustments, we felt, so we decided to blend these two barrels together, and to bottle as a still, single variety cider. Then we blended the steel fermented cider with the cognac barrel, with the intention of bottling as a sparkling cider.

It didn’t take long after bottling for When Burum Met Pomona to be ready to drink, so we were delighted to release the first cider, receiving some really encouraging feedback. Our aim was to release both ciders on Valentine's day in 2023. Unfortunately however we were thwarted by the fact that our sparkling cider… wouldn’t sparkle!

So How Do You Make A Sparkling Cider Sparkling?

There are a number of ways for a cider to be made to sparkle. There's the pet nat method, where bottling takes place before all the sugar in the juice has fermented, there's so-called bottle conditioning, where the cider is bottled with the addition of a small amount of extra sugar dissolved in cider, water, juice or even ice cider, to reboot the fermentation process. There may be yeast still present in the liquid, or a small amount may be included. The "traditional" method, as used with sparkling wine and champagne, takes bottle conditioning one step further, with the spent yeast cells being removed - or disgorged - after secondary fermentation has finished, and a final sugar solution added to taste.

So, for our sparkling cider, we dissolved sugar in the right amount of cider, adding it to the Dabinett cider tank prior to bottling. This tried and tested Little Pomona method, for all intents and purposes should have worked, no question. So it was a shock to all of us, when the time came to open a bottle and nothing happened. Not even a gentle hiss was heard.

Several test bottles later, we eventually made the discovery that there had been an issue with the capping machine, which affixes the crown caps to the tops of the bottles. These caps should be trapping the CO2 produced from secondary fermentation, causing the bubbles to build inside the cider. Unfortunately this hadn't happened, and any gas produced had been slowly flying off into the atmosphere. Thankfully this problem was caught, the ciders were recapped, and our second creation, Sleepless in Bromyard is now a delightfully sparkling Dabinett cider.

We started picking the fruit in October 2021, and by the time the ciders were completed the orchard had gone from bud to flower to fruit, almost twice over. That is an 18 month process! Although cider should be drunk all year round, it is very much seasonal in nature.

The amount of time and energy that goes into producing full juice cider should be celebrated, in the way of other drinks cultures. One of the ways that can help with this is the service of cider, bartenders could be considering what glassware could be used, in what measures could it be poured? As a bartender myself, I’ve been playing around with serving ciders that come in 750ml bottles as 125ml, 175ml and 250ml measures. Similarly with keg conditioned cider and perry, with the additional serving of carafes! This way the higher percentages of full juice cider can be consumed in safer quantities, and although cider is not wine, the shape of a wine glass really helps to amplify aroma.

Being available to work the whole harvest, even just for two ciders sake, had its advantages. Fruit falling and ripening cannot be dictated by a schedule, I was available for all conversations, and ready to pick, sort, and press. Organising the collaboration post harvest was a little like trying to put a cat into a cat carrier, but we got there in the end. Natural cider moves in its own way, and we are very lucky to have been able to witness such a process.

For the full gallery of images head here